As affiliates of the Asociación Internacional de Libre Pensamiento (AILP), representatives of the SSS were invited to speak at the International Conference on Secularism. This year’s title was “La laïcité en Europe ou Europe vaticane ? Concordats ou séparation?”, which took place on 16 December 2018 in Metz, France. Delegates from across the EU attended the conference.

The Asociación Internacional de Libre Pensamiento ( AILP ) is part of the National Federation of Free Thought. Megan Crawford (chair) and Mark Gordon (board member) spoke on behalf of the SSS. The transcripts of their respective talks are reproduced in full, below.

Megan Crawford

Date: 16 December 2017

Problems of Secularism in Europe

Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for inviting Mark Gordon and me to share our Scottish secular perspectives. The first time I met with Philippe and Christine, two things were made clear from our discussions. First, that we share a number of similar perspectives on secularism, theism, skepticism, and free-thinking. The second is that there are any number of different interpretations of what a secular life entails, and the responsibilities of a secular government state. Today Mark and I hope to give you a comprehensive picture of what secularism means to Scotland, and what our shared futures may hold.

The Scottish Secular Society was founded in 2013 by a group of local parents, Mark being one of them. In our 5 years of action, we have remained a non-profit, autonomous organisation sustained financially on donations and memberships, and held together by a passionate group of volunteers.

Last year, however, our society went through a dramatic change in focus. We became a real voice in Scottish politics, successfully petitioned Parliament, and by April 2018 we hope to be a fully recognised charity.

Last year, however, our society went through a dramatic change in focus. We became a real voice in Scottish politics, successfully petitioned Parliament, and by April 2018 we hope to be a fully recognised charity.

We became one of the founding members of the Equalities and Human Rights Advisory Board to Audit Scotland (the financial and budgeting arm of Scottish Parliament and Government) and regularly consult on the Scotland Committee of the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

We became one of the founding members of the Equalities and Human Rights Advisory Board to Audit Scotland (the financial and budgeting arm of Scottish Parliament and Government) and regularly consult on the Scotland Committee of the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

I mention our involvements with policy and Parliament for two reasons. One is to impress upon you the recent and very real shift in the narrative surrounding Scottish politics. Ministers of Scottish Parliament and Councillors have historically remained off limits to organised secular voices. Scottish law holds privileges for religion, particularly Christianity, in education, taxes, charity services, and unofficially in nearly every aspect of Scottish life, including media, television programs, public business hours, public transportation, even dictating when children can play in public parks. So for Parliament to be willing to have a dialogue with a national secular organisation shows how dramatic the narrative is shifting in Scotland.

The other reason I mention our policy involvement is to highlight where our work is presently focused. In Scotland, as in many places in the world, the last bastion of protected religious hold is in education. As with many of our home countries, the school system in Scotland began under religious rule and was the first to make education compulsory, with the Education Act of 1496. The Education Act has gone through several amendments over the centuries, and these largely have amounted to a slow and steady process of replacing the monopoly that religion held, with an ever-growing management by the parents and state. The church, though, did not loosen their grip on education easily, and managed to ensure their permanent presence in all schools, both non-denominational and denominational.

The other reason I mention our policy involvement is to highlight where our work is presently focused. In Scotland, as in many places in the world, the last bastion of protected religious hold is in education. As with many of our home countries, the school system in Scotland began under religious rule and was the first to make education compulsory, with the Education Act of 1496. The Education Act has gone through several amendments over the centuries, and these largely have amounted to a slow and steady process of replacing the monopoly that religion held, with an ever-growing management by the parents and state. The church, though, did not loosen their grip on education easily, and managed to ensure their permanent presence in all schools, both non-denominational and denominational.

Today, the church’s educational privileges are focused in three areas. The first is in the curriculum. The second is in governance. The third is the continued presence of denominational schools, which are largely Roman Catholic. The remainder of my talk today will discuss our efforts in each of these areas.

Arguably the loudest and most contentious battle right now surrounds the church’s iron grip on school curriculum. As part of the church’s agreement to hand over control to the state, provisions were made to require all primary and secondary schools to teach religious instruction. Today, this instruction is divided between two courses. One is Religious & Moral Education and the other is Religious Observance. The latest Education Governance Review states the following about Religious & Moral Education (RME),

Arguably the loudest and most contentious battle right now surrounds the church’s iron grip on school curriculum. As part of the church’s agreement to hand over control to the state, provisions were made to require all primary and secondary schools to teach religious instruction. Today, this instruction is divided between two courses. One is Religious & Moral Education and the other is Religious Observance. The latest Education Governance Review states the following about Religious & Moral Education (RME),

Education about faith and belief in [all] schools… contributes to the development of the whole person… It increases children and young people’s awareness of the spiritual dimension of human life through exploring the world’s major religions and views, including those which are independent of religious belief, and considering the challenges posed by those beliefs and values.

This sounds nice enough at first reading, but the assumption of a Christian flavoured God and human ensoulment is clear in the language, and reflects the assumptions that leak directly into the curriculum. For example, that passage assumes there is a ‘spiritual dimension’ of those with no religious belief, including atheists. The Education Governance Review says the following about Religious Observance (RO),

This sounds nice enough at first reading, but the assumption of a Christian flavoured God and human ensoulment is clear in the language, and reflects the assumptions that leak directly into the curriculum. For example, that passage assumes there is a ‘spiritual dimension’ of those with no religious belief, including atheists. The Education Governance Review says the following about Religious Observance (RO),

[RO entails] community acts which aim to promote the spiritual development of all members of the school’s community and express and celebrate the shared values of the school community. RO needs to be developed in a way which reflects and understands Scotland’s diversity. It should be sensitive to our Christian traditions and origins and should seek to reflect these but it must equally be sensitive to individual spiritual needs and beliefs, whether these come from a faith/belief or non-faith perspective.

Again, we come across the assumption that atheists and humanists must necessarily have spiritual needs and beliefs, and that all students, in fact, require ‘spiritual development’.

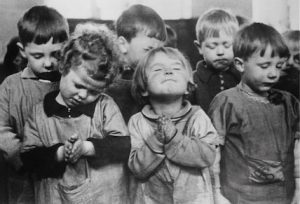

The exact curriculum that is developed for RME and RO courses is left to the discretion of the school. The school, or head teacher, often turns that responsibility over to the local churches and volunteers. What this has amounted to is a long and twisted practice in Scotland of unregulated mandatory religious instruction to all students.

Parents, students, and to a lesser extent, teachers, regularly approach our society with stories of religious privilege being abused in their schools. We offer them support, but all too often there is little follow-through. Parents fear their children and family being bullied or shamed if they question the religious abuses. They fear these things because this is precisely what has happened when students and parents stood up and demanded their schools follow the law.

One mother was openly attacked on Facebook, in a group for teachers and parents of a non-denominational school in east Scotland. She asked why there needed to be prayers in her son’s school given that it is non-denominational. The biggest voice of opposition actually came from one of their local Councillors, who sat on their Education Committee. He used guilt and shaming techniques, which progressed quickly enough into abusive accusatory language. This is how comfortable Christian control is, in Scotland’s education system.

The biggest issue parents come to us with is attempting to exercise the ‘conscience clause’ provided with the religious education statute. This clause allows any parent to withdraw their child from all religious courses and activities at school. Schools are required to respect parents’ wishes, and to have meaningful, alternative activities for all students withdrawn from religious activities. Along with this, the law states that no child is to be harmed from being withdrawn.

This, sadly, is too often not how things work out in real life. Schools fail to inform parents that they can withdraw their children from religious activities. Some schools hold several prayer sessions a day. Head teachers try to coerce parents to keep their children enrolled in religious courses. Sometimes this comes from the teacher as well. And some of the alternative activities for removed students have terrible and traumatizing consequences.

One little boy, age 7, was sat alone behind a glass wall on display for his whole class to see him while they playfully participated in a religious interactive sermon at school. The teachers did not supply him with any materials or activities, and no one supervised him. This boy was bullied and verbally abused later by other students in the class because no one explained to the children why he sat out of the lesson, and no one supervised the children or discussed the diversity of their group, so some of the children thought the school had decided he was too strange to be included with the other kids anymore. This boy has had nightmares for months.

Another boy, age 5, brought up in Turkey by atheist and agnostic parents, went to a church for the first time in his life, during a religious assembly at his primary school in Scotland. The parents were unaware that their son’s class was visiting a church. The volunteer who told the Easter story had such poor training on how to communicate with children that she traumatized this young boy. To him, the story was about a man who had been tortured and murdered, and that everyone who doesn’t believe in this man is a bad person. This little boy went home incapable of talking to anyone for hours, couldn’t eat his dinner, and had nightmares every night for the following week. “He hurt” and “there was so much blood” are two phrases this little boy kept repeating over and over once he finally started talking with his parents.

There are thousands of similar stories. In these two cases, like the majority of the ones that are brought to our attention, little to nothing is done to fix the situation. Head teachers take too little responsibility for the religious component of their schools. And the law protects them from being forced into any further action.

At the policy level, we are staunch advocates for the removal of RO in schools. However, the entrenchment of the church in public policy means that no Scottish politician would ever allow a voice to anyone petitioning for the full removal of RO. So our society took a different tactic, and Mark Gordon, as a local parent with the support of the SSS, filed a petition in Parliament to change the rules. Mark will tell you about his campaign in just a minute.

The other major issue we run into are the regular appearances of illegal Christian fundamentalist literature in schools. There’s been a rush of seemingly unlimited funding from American fundamentalist ‘megachurches’ behind a lot of this, too.

The other major issue we run into are the regular appearances of illegal Christian fundamentalist literature in schools. There’s been a rush of seemingly unlimited funding from American fundamentalist ‘megachurches’ behind a lot of this, too.

Our latest campaign focused on the policies behind higher-ranking religious privileges. The whole of Scottish education is overseen by 32 Education Committees. All seats on these committees are elected except for three, which must be filled by a representative from the Church of Scotland, the Roman Catholic Church, and any other religion within the school’s local community. Often, this is filled by another church representative, creating a Christian monopoly on most Education Committees.

The Scottish Secular Society petitioned Scottish Parliament for the removal of this theocratic anomaly. We requested that the seats remain, but become subject to the same democratic voting process as all the other seats. As the law stands, the religious voices are mandatory and given equal voting strength as all the other elected committee members. The most shocking revelation from our petition work was that almost no one knew of this mandatory religious members for schools. Unlike previous work, we argued from a democratic equality platform. The response we received from Scottish Parliament and Government showed us that this appeared to be the right platform to strike.

We received a enough public support that Parliament agreed to hear our petition last year, then forwarded our request to Scottish Government. A final decision is still pending, but the Scottish Government stated that it will,

Seek to undertake an Equality Impact Assessment on any policy proposals emerging from the Education Governance Review. It is our intention that once this process has been undertaken we will then consider any of the Scottish Secular Society’s proposals that are not addressed through any changes made by the Education Governance Review.

The Education Governance Review was just published, and nowhere in the document does it directly address the mandatory unelected religious representative seats. Which means there is little chance the Equality Impact Assessment will bear any usable fruit on the topic. And therefore, we will address Government for a second time, to ensure they follow through with their stated considerations.

The picture of Scotland today is one of a majority non-religious, liberal minded, and proud people. The Scottish Government, however, is still in a tangled dance with archaic Christian laws and contemporary demands of equality. As a secular society, we are here to help them untangle.

Mercí.

Mark Gordon

Date: 16 December 2017

“Religion in the Classroom – A Citizen’s Petition.”

INTRODUCTION

I would like to add my thanks – to Megan’s – to the IAFT for inviting the Scottish Secular Society. I am one of the founding board members of the Scottish Secular Society and I was instrumental in kicking off our first major campaign, on the topic of Religious Observance. More of that later. I now live and work in Switzerland, but since I have many family members still living in Scotland I think I can safely reserve the right to remain concerned about what goes on there. In the present moment, Brexit and Independence are to the fore, but more generally the secular landscape – the nexus of religion, education and the law – is my particular field of interest.

As many of you will be aware, Scotland and France have a long history of alliances – the height of that being the 15th century, where for example the Garde Écossaise – The Scots Guard – fought alongside Joan of Arc against England and Scottish intervention arguably contributed to French victory in the Hundred Years War. I hope that many more alliances – albeit of a more peaceful nature – can be forged this weekend. I am also aware that Metz itself has been – twice to my knowledge – a place that has been a turning point or a pivoting in world events. Perhaps our convention this weekend can be a far more positive turning point in world affairs.

Today I would like to focus on the Scottish Secular Society’s first official campaign in 2013 and present to you what I believe are key points of detail in that. I hope that, from these observations you might obtain some insight into how a secular campaign can be successful – or not. And of course I hope that these lessons can be taken and applied in your own campaigns, whatever they may be.

First, however it is essential that I provide – for those who don’t know – a little background – the religious and historical landscape in Scotland, if you will.

Historical Background – The Religious Landscape in Scotland

Scotland is a land full of beauty and contradictions. To the north and west there is a rugged landscape – the mountains and glens of the highlands. To the centre there is an industrial heartland and further south, rich farming land. We have fish, oil and renewable energy sources off our coasts.

Our people are an attractive and clever lot too. In the past, the Scots have brought you, amongst other things, the steam engine, tarred roads, the tyres for your cars, penicillin, television and whisky.

But all of that cultural and technological success had to have a beginning. And these were beginnings undeniably entwined with the waxing and waning of various religions. And whilst Scotland’s journey to become a distinct nation can be said to have stretched from the 6th to the 14th centuries, religion in Scotland of course appeared much earlier.

During the Roman occupation and mainly in the 5th Century, Scotland had an influx of Christianity from Irish missionaries such as Ninian, Kentigern and Columba. This Irish Scottish Christianity – or Celtic Christianity – had some key differences from the Roman faith e.g. Date of Easter, Tonsure as well as an emphasis on Monasticism rather than a Diocesan structure.

By the 7th Century, this Celtic Christianity had aligned with the Roman church (2) and by the Middle ages – in the Norman period – Scotland saw the development of more formal parish structures. The Scottish church established its independence from England, developing a clear diocesan structure and becoming a “special daughter of the see of Rome”

Gradually moving towards the 15th century, monasticism declined and bishoprics were established with new Saints and devotional cults proliferating.

Then came the Protestant Reformation. An upheaval, part of the blame of which can be laid at the doors of a certain Frenchman, Jean Calvin. Part of a wider European Reformation, the Scottish Reformation created a predominantly Calvinist national church – or Kirk – which was strongly Presbyterian in outlook. Papal jurisdiction and the Roman Mass were then rejected by the Scottish Parliament in 1560 and became illegal. England had already separated from the Roman church in 1534

When the sixteen year old Francis II of France died in 1560, his wife Mary Queen of Scots returned to rule Scotland. Her mother, Mary of Guise had been regent of Scotland during her daughter’s absence from the French court and her main goal had been a close alliance between the powerful French Catholic nation and the much smaller Scotland, which she wanted to be Catholic and independent of England. A secret clause signed by Mary Queen of Scots provided that Scotland would become part of France if the royal couple did not have children.

In what can easily be described as serious mismanagement, Mary, considered a legitimate claimant to the English throne by many English Catholics, got through two further husbands and in the power struggle that ensued – not helped by a Papal Bull from Pope Pius V calling on Catholics to rebel against her cousin Elizabeth I – she was finally executed at her command. By the end of Elizabeth’s rein in 1603, Catholicism in England and indeed in Scotland was in massive decline, with worship at time being necessarily conducted in secret.

By the late 18th century however, the Church of Scotland – the Kirk – began to fragment around issues of patronage, government and reflecting a wider polarisation of beliefs between moderates on the one hand and evangelicals on the other. This polarisation of beliefs resulted finally in what is called The Great Disruption of 1843 which saw roughly a third of the clergy, mainly in the North and Highlands, break away to form the separate Free Church of Scotland. Later in the 19th century, debate between fundamentalists and theological liberals resulted in further splits. Although there were moves towards reunion of the churches – and most of the Free Church rejoined the Church of Scotland in 1929 – these schisms left many small denominations on the religio-cultural landscape.

With the process of Catholic emancipation that started in 1766, the Catholic Relief act of 1829 saw and end to the outlawing of Catholicism in the United Kingdom (the Union of the two kingdoms of Scotland and England having been formed in 1707). Perhaps unsurprisingly, this provoked anti-Catholic riots across the country. This sectarianism continued to fester, helped least of all by a massive influx to West and Central Scotland of Irish Catholics. This immigration had been the result of extreme poverty effected by the previously mentioned anti-Catholic legislation at work in the island Ireland itself which was at that time part of the United Kingdom. It is estimated, for example, that between 1841 and 1851 the Irish population of Scotland increased by 90%. Later, Italian, Polish, and Lithuanian immigrants reinforced those numbers.

The Education (Scotland) Act 1918 sought to address what had now become a two tier system of education. In 1917, the bulk of Scottish schools -originally parish schools set up mainly by the Church of Scotland were “board schools” – run by the school boards. And they benefited from financial support from the local taxes. Although board schools were subject to a ‘conscience clause’ by which parents could opt their children out of any religious education, the Catholic community and parents chose to establish more than 200 ‘voluntary schools’. Prior to the Education Act these schools received some central funding, but no assistance from the local taxes – which of course Catholic parents still had to pay. This is unfair even to a secularist.

It was not until 1980 that the Education legislation was updated and revised in Scotland and guidance notes issued that offered a slim level of protection for the non-religious.

This is all to give you some idea of what a complicated religious landscape existed then and still exists today. I should point out that whilst anti-Catholic sentiment does remain in Scotland to this day it is very much diminished and it is now very hard to argue that Catholics in Scotland are at any particular disadvantage on account of their faith.

All this sits against a continual background of falling adherence to faiths and falling weekly attendance. So what are the figures? Well, what we can see now is that those of no-faith – and we know that this is underestimated to some degree – have steadily increased from around 40% at the turn of the millennium to around 60% now. In theory, we should now be a fully secular nation. The reality is not quite like that however.

Petition PE01487 to the Scottish Parliament.

What was the thinking behind our campaign?

We now move forward to 2013, when I personally moved from being just another “angry atheist on the internet” to someone who wanted to affect real meaningful change. The reason? I now had a 5 year old daughter who would be attending school for the first time. I had read the 1980 Education act and the associated guidance documents and I knew my rights. I told the school that I didnt want her to take part in Religious Observance specifically mentioning that she was not to be taken to church or allowed to attend assemblies where the local minister would be pontificating. For a while all was well.

Then, unaware of my written instructions, a member of the school staff took her to a church service. Of course I was furious and I realised that what we had on our hands now was the perfect opportunity – a test case if you will – to raise the matter at some official level.

Of course, as that “angry atheist on the internet” I wanted to do something – most likely get rid of religion from schools altogether. In those early days, my Scottish Secular Society colleagues and I had been doing a lot of talking – perhaps too much talking – and I came to the conclusion that if we carried on talking, nothing would be done. We must move from talking to action.

What could we do? We had a situation where Scottish children are educated in one of two kinds of school. Denominational schools (Catholic schools + 3 Episcopalian schools + 1 Jewish school). And then we have the so called “non-denominational” Schools.

Contrary to the understanding of a large number of parents, non-denominational in the Scottish context does not mean non-religious or secular. In simple terms it really means “non-Catholic”. Because of the history of religion in Scotland that I spoke earlier about, that means in most cases, these non-Catholic schools will have a general alignment to the Church of Scotland or in the Highlands and other remote areas, an alignment with the Free Church of Scotland. The extent to which Scottish children are exposed to religious proselytising varies across the country – often depending on the faith of the head teacher.

Now it also needs to be repeated that there are two areas where a child is exposed to religion in Scottish schools.

First there is Religious Education (Variously abbreviated to RE, RME, RMPS or RERC – in common parlance RE.)– which is the study of religions in a comparative fashion. In this, according to Scottish Government guidance (Ref) there should be no favouring of one religion over another or over non-belief. The Scottish Secular Society believes that well conducted Religious Education ABOUT the various world religions and world-views is an essential tool in raising children today. How, for example, can we understand Islamism if we first do not know anything about Islam? How can we be better friends with the Sikh who lives next door if we know nothing about what he believes in?

Then there is Religious Observance (RO) – sometimes called common worship. This also, according to guidance from government should be non-confessional and inclusive. We know from experience that this guidance is rarely followed and what goes on in schools is very much down to the wishes of the head teacher and the influence of the churches local to the school.

In denominational or “faith” schools, the law simply says that proselytising for one religion – Christianity – is to be expected and whilst a child may legally be opted out of either or both RE and RO in these mainly Catholic schools, it is almost impossible to extract the child fully from experiencing this as the Catholic faith is often imbued into every lesson of the day.

All that went on in Scottish schools then, was governed by the Education Act (Scotland) of 1980 and we looked again at the act to see if there was something we could actually change.

Of course asking a whole nation to drop religion in schools completely overnight was not going to happen. We knew that such a battle was not winnable. The SSS had meagre resources and the opposition, the churches, were very well funded, very active in the media and there were many – there still are – members of the Scottish Parliament who remained beholden to one faith or another. Sadly, what we needed was a more gradual approach. The question was, which approach?

Examining the law and the reality on the ground we found mismatches. So what does the act and its associated guidance circulars actually say?

Amongst other matters, the Education (Scotland) Act of 1980 :-

- Enshrines in law, religious education and religious observance. The effect of this is to permit indoctrination to varying degrees across the country.

- Includes a “conscience” clause (Clause 9 of the 1980 Act) which allows parents to opt their children out of either Religious Observance, Religious Education or both.

- Provides that the religious nature of education may not be removed unless a poll of the local authority electorate approves. (This presents an unduly onerous task to any committed activist wishing to change the law and I think its inclusion is quite undemocratic – no local authority wishes to spend a good deal of money on something that has potential to upset a large portion of its citizens.)

Additionally, there are guidance notes sent by central government to schools outlining how the law should be adhered to. The language used in these guidance notes makes it all to easy for a head teacher to play fast and loose with the original intent of the legislators.

What we needed to do – if we could not remove religion from schools – was to weaken the hold that it has. With that in mind I devised a strategy that I thought could be acceptable to many – including perhaps organised religion.

Our petition sought to change the Education (Scotland) Act 1980 so that children are not automatically opted into Religious Observance by the school. It asks instead that parents are given an active choice between Religious Observance and a suitably meaningful alternative activity. In essence, we want the parents to be asked first. In other words all parents would have to opt their children in to Religious Observance rather than them being automatically included and them having to opt out.

And here was the spin. Our most vociferous opponents claim us to be an atheist group or an anti-religious group masquerading as secularists. We said, “No – here is the proof that we are not. We don’t want to remove religious observance. In fact we want to allow it to become something that parents make a deliberate conscious decision to opt IN to rather than something that children were forced to endure. If anything, the quality of Religious Observance should improve.”

Why that approach? Why not seek full removal? Well principally 2 reasons.

Firstly, I think we should pick to engage only in winnable battles. At the time evidence did not support the case that the majority were non-religious (Although only just, at around 47%). Religions were well funded and organised and we knew they would put up a strong fight. We knew that they would have many allies in government. We had few. It didnt make sense to start a fight that at that moment we would lose.

More importantly – and this is a personal opinion and a particularly difficult one to express here of all places, in a country that is possibly as free from religion as a country can be – I think it is not the job of Secularism to remove religion from the public space.

Secularism is NOT atheism or anti-theism. I think it behoves us to ponder upon the nature of secularism. Where it comes from. I believe Secularism stems directly from the various expressions of human rights we have all agreed upon. And I think that its fundamental meaning is that state and religion should be separate and that there should be freedom from religion as well as freedom for religion.

By this I also mean you should to try to consider the rights of the religious as well. Not the sickening privileges, that Megan previously mentioned, but the rights. Surely if a parent wishes a child to have Religious Observance then it is not unreasonable to afford some access to that as part of the child’s education. Whether we agree the state should pay for it, is another matter.

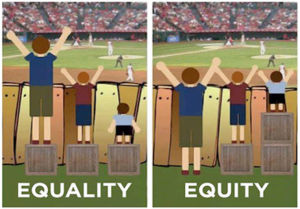

Take a little time to consider this:-

On the left we see three children that have been given equal assistance. Despite that, one child is disadvantaged. On the right, we see the same three children that have been given different levels of assistance but the outcome is positive and equal for all.

The same thinking, I believe should apply to situations where you want to remove things in order to protect children.

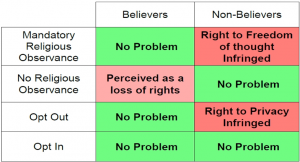

The following table shows the possible outcomes concerning Religious Observance in schools:-

We can all too easily debate the outcomes, but it is clear to me that the only situation where the well being of all children is maximised is where Religious Observance is on offer to those that want it, if they opt in. If they make an active and informed choice to be part of something rather than being coerced.

There were many interesting and sometimes tortuous arguments given by the religious lobby on that thinking. Most of all, we were accused of being disingenuous and that “it was all just a slippery slope towards a Communist Atheist Secularist Utopia.” But I believed that being up front in this fashion would gain us some sympathy even from some amongst the religious. And to an extent it did.

The Outcome of our Petition.

We had our day in parliament and it truly was inspiring to find myself as an ordinary, albeit motivated citizen speaking directly at and to the seat of governance of our country. At the first sitting we were able to present our arguments, which you can read in the petition document. At the second sitting the matter was passed to the Education and Culture Committee which considered the matter further and asked Government a lot of searching questions.

Ultimately however, government decided that no action should be taken to change the law but that more effort be made to ensure that schools are compliant with legislation. We continue to hear about low levels of non-compliance from concerned parents and we know that in certain areas of the country, government guidance notes are routinely ignored.

One could take this as a lost battle. However, we do not.

Firstly, we significantly raised the profile of our society – often becoming the media’s go-to spokespersons for the secular side of any debate on religion in society. Secondly we gave notice to the country and government that no longer was religion to be “sacrosanct” and that it would be challenged. Thirdly our arguments clearly brought a lot of information out into the open that many would not have heard of. e.g. How endemic was the poor provision of meaningful and alternative activities for those opting out, or the fact that only 20% of parents were informed by schools that they had a right to opt out and that only 40% overall knew they had a right at all.

We learned a lot too. We met some surprising allies. Many MSPs came out as closet secularists. Many Christians came out as closet secularists. Many religious characters however remained true to type with one or two being particularly vociferous, self-serving and nasty. We learned that a lot of time could be wasted engaging with these characters and that by debating with them on public forums – in media comments sections, on Facebook and the like – we were merely giving them the oxygen of publicity they desired.

[END]